I was born in Berlin in 1928, although, because my parents moved about so much, I spent just the first and the last six months of my German life there. It was when the Nazis moved into the Rhineland that I first became aware of them. I remember standing by the roadside when the soldiers marched in.

We lived in Cologne at this time where I attended a Jewish Kindergarten. We had a maid who looked after me while Mum, unusually for that time, had a full-time job. As time went on I realised things were not as good as they should be. Mum and Dad were becoming increasingly worried. When I was about six years old, I noticed newspaper hoardings saying unpleasant things about the Jews. We had a radio and I can remember hearing Hitler’s strident voice.

Around 1935-7 I was still at a State school, where I was not treated too badly. As I had red hair, I was always being teased anyway! During this time Jews were not allowed to sit on park benches, go to swimming pools, the theatre or cinema and gradually Jews were deprived of their citizen rights. My father then went to Berlin to retrain as a chiropodist/masseur as he thought it would make it easier for us to emigrate if he had a profession rather than being a businessman. Up to this time all his applications to emigrate had been unsuccessful. Mum got a job some 300 miles from Berlin and she and I lived there for about six months. When Dad qualified, Mum and I rejoined him in Berlin in September, 1938, when I was 10. He was only allowed to take Jewish patients and had a rubber stamp which said ‘Chiropodist to the Jews’.

Accommodation in Berlin was very difficult to find for Jews. We were able to live with a cousin of Mum’s who worked as a caretaker to a Jewish school and who had spare rooms in his flat. I was also able to attend that school. At the beginning of November I remember seeing newspaper hoardings declaring ‘von Rath shot’. Dad said ‘That means trouble’. On the night of 9th November I was awoken by my parents and the cousins rushing about, but they wouldn’t tell me what was wrong. In the morning my parents told me that we could not stay with the cousins, we packed a bag and went out into the street where I saw glass everywhere. There were many policemen and Nazis jeering while Jews swept up glass and boarded windows. All that day we were constantly on the move, walking, taking buses and the tube. I saw synagogues in flames and also an old man sitting in his cart with his books burning around him. Dad felt that he might escape arrest by never stopping anywhere for long. That evening we went to stay in a flat which my mother’s best friend had just left as she had emigrated to England. She had given the key to Mum. This empty flat was just above a police station and Dad thought we would be safe there. Mum and I crept up the stairs and once in the flat Mum twitched the curtains to tell Dad in the street that all was clear. After a while, things simmered down and we did find a flat.

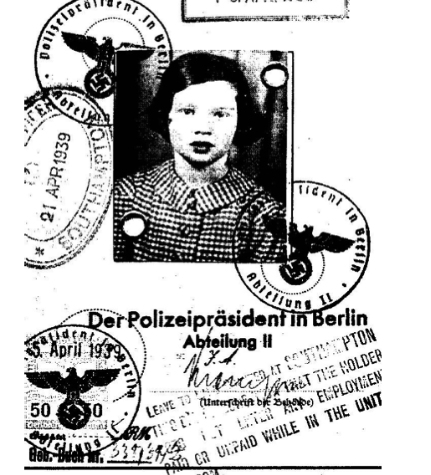

In England at this time, the organisation known as Kindertransport had been set up. Rabbi Dr Israel Mattuck of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in St John’s Wood asked his congregation to consider taking in children from across Europe. Consequently, through a series of coincidences, it was agreed that I would be looked after by two sisters, Millie and Sophie Levy, who were social workers in the East End. We exchanged many letters and sent photographs. I was enrolled on the Kindertransport list and when my name came up in April 1939 my parents took me to the railway station where there were many parents and children in tears. We, however, pretended I was going on a marvellous adventure. Later as the train passed through a station, there were my parents, frantically waving to me. I was 10 years old; that was the last time I ever saw them.

We boarded an American ship at Hamburg and arrived in Southampton. Once there, we boarded a train for London and at Waterloo, wearing labels round our necks and carrying only a small suitcase, we waited for our names to be called out. When my name was called, I went to the barrier and there were these two ladies whom I recognised from the photographs. In addition to my school lessons, Mum had taught me some basic English so I managed to get by. At first, the ‘Aunties’ sent me to a Boarding school, which I hated, but later I was able to go to South Hampstead High School, which I enjoyed attending for the rest of my school life. There were quite a few other Jewish children at the school, many of whom were also refugees. I was able to write to my parents two or three times a week before the war. Once war had started, we were only allowed 25-word messages once a month each way through the Red Cross. In December 1942 we received a message from Dad which said, ‘Sorry bad news. Mummy emigrated 14th December. Am terrified myself but confident of family reunion after the war’. In January there was one further message, but after that there was complete silence.

At 18, I wanted to go to university, having achieved the required grades, but the Aunties would not allow this. They maintained that if, by some miracle, my parents had survived the camps, I would have to be in a position to support them, and so they sent me to a good secretarial college. At the time I was most unhappy, but later came to see how wise they had been and how fortunate I had been to have been in their care.

Ann met Bob Kirk, another child of the Kindertransport, at a club for young Jewish refugees, run by Woburn House. They were married on 21 May 1950.

Today both Bob and Ann work tirelessly to raise awareness of the Holocaust and the experience of the Kindertransport through speaking at activities for Holocaust Memorial Day and throughout the rest of the year. They have two sons and three wonderful grandchildren.