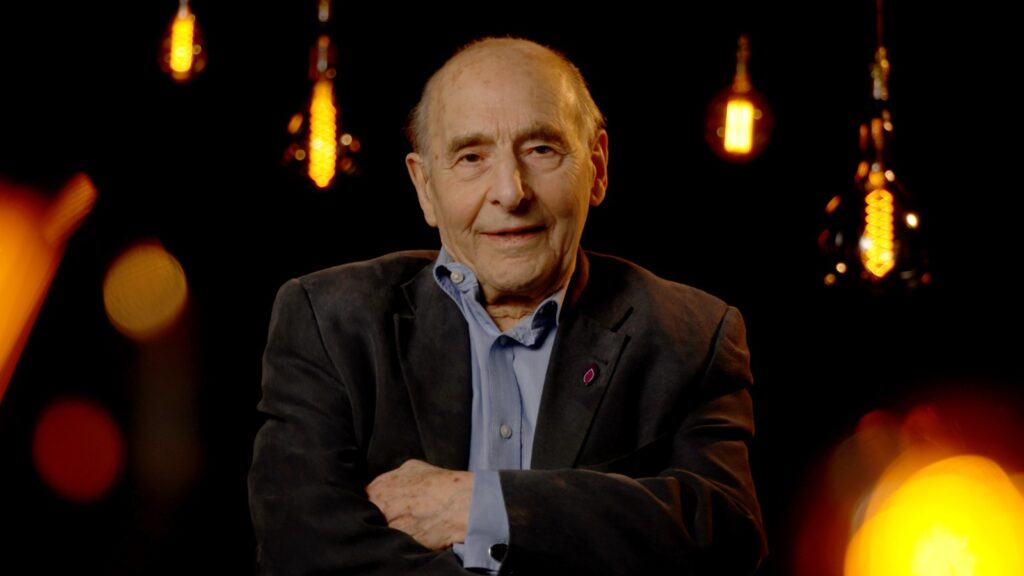

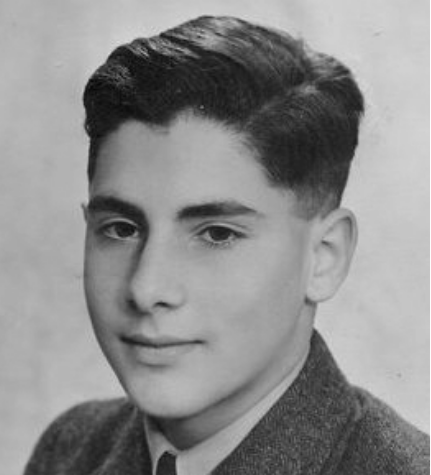

I was born in Hanover in 1925, the youngest of three children. My father’s family had been cattle dealers in southern Germany for generations. I can trace the family tree back to about 1700. My father and uncles were among the first generation to leave the business and the village. Father went to school in Heidelberg, and then he studied textiles in Frankfurt. My parents married in 1912 and settled in my mother’s home town, Hanover, where Dad established a textile business.

My early childhood was comfortable and I started school in 1930, but as soon as the Nazis took power in 1933 everything changed. New regulations were constantly imposed, making life for Jews more and more difficult. School was not too bad, until I started secondary education in 1936. Then there was much more bullying; my classmates were under orders not to associate with Jews – and usually we were made to sit at the back and not participate in the lesson.

The question of emigration was often discussed, people were leaving all the time but my father resisted the idea for a long time. He had fought in the First World War with some distinction and thought, like many others, this would count for something and keep us safe. My sister, who was 11 years older than me, thought otherwise and left for South Africa in 1936. Eventually my parents too started to try to find ways of leaving. One real obstacle to emigration from Germany, at that time, was a very high exit tax. The greater difficulty was to find a country to which to go. Almost all countries worldwide had economic and labour problems and did not allow unlimited immigration. Some required a guarantee from a resident, certifying that the intended immigrant would not rely on state social services. Others had quotas — limits on the number of people allowed in each year. My parents made many applications, but all were refused.

In November 1938 the Nazis organised a major pogrom, when hundreds of synagogues throughout Germany and Austria were destroyed, homes and businesses attacked. That pogrom became known as KristallInacht— the night of broken glass. 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps. After that, all Jewish children had to leave state schools. Of course, the Jewish schools became very overcrowded. It was now clear the Jewish community was in great danger. The British parliament agreed that 10,000 unaccompanied children could be admitted to the country. An organisation called Kindertransport (Children’s Transport) was set up to deal with this. They collected the names of those who wanted to come, organised transport, provided people to accompany the children and found places for them to go.

On 3rd May 1939, aged 13, I left Hanover and travelled to England via Holland. The first stop inside the Dutch border was wonderful. We were met by kind people with drinks and food — and smiles. There had been no smiles from a grown-up outside the family for a long time. My transport went to Liverpool Street. We were taken to a large underground hall, where we all sat on our little suitcases, with name labels round our necks, and waited to be called for. I was collected by a gentleman by the name of Smith – that is all I ever knew about him — and taken to a beautiful house in Hampstead, where I was handed over to the housekeeper. Mr Smith was a very generous man. Every child had to have a guarantee of £50; he had sponsored six of us to the tune of £300— quite a lot in 1939. Each of us stayed with him for a week or so until the next one arrived, and then we had to move on. This was fair, but I had not known it would happen. At this point I did not speak English, so perhaps I just had not understood what had been said. Next I stayed with a family in Greenford, the Morris family who had two young children of their own. They sent me to school, where I started to learn some English. The first lesson, luckily, happened to be poetry, which caught my imagination.

This family had also sponsored another boy, and when Henry arrived it was a case of ‘we would love to keep you, but …’ The Morris family emigrated to Canada eventually, but we are still in touch. Following this I went to a hostel at Westgate in Kent. I have no idea how many of us there were, it felt like hundreds. There was nothing for us to do, no thought seemed to have been given to keeping us occupied. Eventually, at the end of August, I returned to yet another hostel in London, just in time to join a school and be evacuated at the beginning of the war. We were sent to Whipsnade — and there was a re-run of our Liverpool Street arrival. The children sat on their cases on one side of the village hall with the local people on the other side, and we waited to be chosen. In the end just three of us, all refugees, were left and a couple of very kind ladies, sisters, who ran a chicken farm, took the three of us. The evacuees became the village school, absorbing all the local children who, up to that time, had been taken by bus to other villages for their education. We had arrived with three teachers, but shortly after, two were called away, leaving one lady to look after the whole range from infants to near school-leavers. Two of us, myself and another older boy, were drafted to do some teaching. I stayed at school until 1941, I was 16 and was then directed into war work in a factory making instruments for the Navy and RAF. I also joined the Home Guard. In 1944 I joined the Army, and eventually became an interpreter dealing with German prisoners of war.

Up to the outbreak of war, my parents and I had been in constant touch. That soon changed, and we were restricted to 25-word messages once a month via the Red Cross. Those messages stopped in late 1941, and after the war I found out my parents had been on the first transport out of Hanover, on 15 December 1941, to a concentration camp in Riga, Latvia. They never returned.

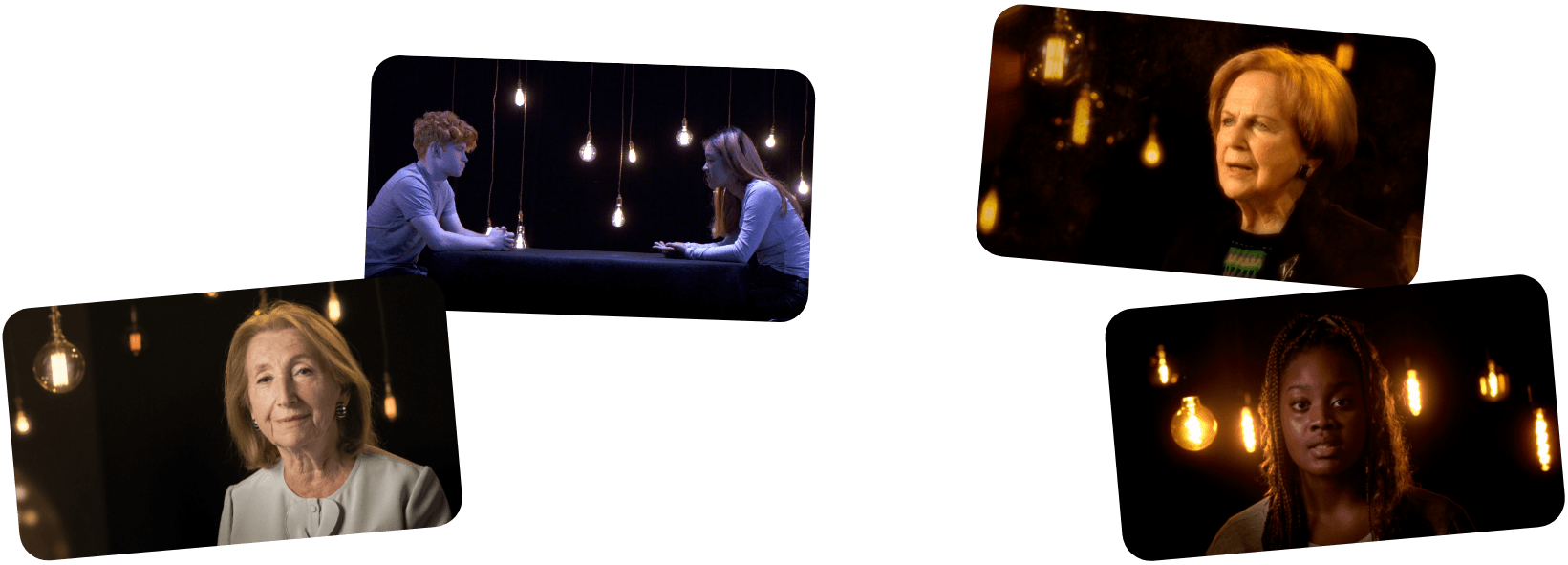

Bob met his wife Ann, another child of the Kindertransport, at a club for young Jewish refugees, run by Woburn House. They were married on 21 May 1950.

Today both Bob and Ann both work tirelessly to raise awareness of the Holocaust and the experience of the Kindertransport through speaking at activities for Holocaust Memorial Day and throughout the rest of the year. They have two sons and three wonderful grandchildren.